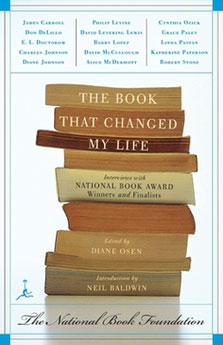

The Book That Changed My Life: Interviews with National Book Award Winners and Finalists

Every reader can name at least one book that changed his or her life—and many more beloved titles will surely come to mind as well. In The Book That Changed My Life, fifteen of America’s most influential authors discuss their own special literary choices. These unique interviews with National Book Award winners and finalists offer new insights into the many ways in which the experience of reading shapes the act of writing.

Robert Stone on Joseph Conrad’s Victory, Cynthia Ozick on Henry James’s Washington Square, Charles Johnson on Jack London’s The Sea-Wolf—each approaches the question of literary influence, while offering rich and wonderful revelations about his or her own writing career. James Carroll, Don DeLillo, E. L. Doctorow, Diane Johnson, Philip Levine, David Levering Lewis, Barry Lopez, David McCullough, Alice McDermott, Grace Paley, Linda Pastan, and Katherine Paterson are the other distinguished contributors to this collection of informed, insightful interviews.

Chapter 1: James Carroll

James Carroll, Winner of the 1996 National Book Award for his memoir An American Requiem: God, My Father, and the War That Came Between Us, was born in Chicago in 1943 and grew up outside Washington, D.C., where his father worked as an FBI agent. After joining the military, his father became a lieutenant general in the air force and director of the Defense Intelligence Agency. Carroll attended Georgetown University before entering St. Paul’s College, the Paulist Fathers’ seminary in Washington, D.C. After his ordination to the priesthood in 1969, he served as the Catholic Chaplain at Boston University for five years before leaving the priesthood and pursuing a career as a writer. In the years since, he has published nine novels, including Mortal Friends, Prince of Peace, and The City Below, and written a weekly op-ed column for The Boston Globe. In his most recent book, the critically acclaimed Constantine’s Sword: The Church and the Jews, he chronicles the two-thousand-year-old battle of the Church against Judaism, while confronting the crisis of faith this tragedy has provoked in his own life.

A Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a member of its Committee for International Security Studies, Carroll is a former chair and current member of the council of PEN/New England, as well as a Trustee of the Boston Public Library and a member of the Advisory Board of the International Center for Ethics, Justice, and Public Life at Brandeis University. He has held fellowships at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and at Harvard Divinity School. He remains an Associate of Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, where he is at work on a history of the Pentagon. His tenth novel will be published in 2003. He lives in Boston with his wife, the novelist Alexandra Marshall, and their two grown children.

Hailed by the judges of the 1996 National Book Awards as a “flawlessly executed” memoir, An American Requiem tells the story of James Carroll’s transformation from a passive, politically conservative seminarian into an outspoken critic of the war in Vietnam and proponent of civil rights-a transformation that divides him from his father even as it brings him closer to God. An unforgettable account of a son’s struggle to claim his own political and religious identity, An American Requiem reveals that, in the author’s words, the “very act of storytelling, of arranging memory and invention according to the structure of narrative, is by definition holy. . . . Telling our stories is what saves us; the story is enough.”

Diane Osen: You write in An American Requiem that as a young seminarian you started composing poems and stories to help salve your soul. Why do you suppose you turned to writing, instead of something else, to find that relief and release?

James Carroll: It was the accident, I suppose, of being in a setting in which reading and writing were at the heart of what I was doing, as opposed, for example, to being in the world of business, or the military, or some other career. I wasn’t raised to be a book person, and to find myself in a world where I was expected to read seriously and write seriously in an academic setting, well, it was a first-time experience for me. Before entering the seminary, I had not encountered the life-changing potential of reading as a source of meaning, as a way of ordering one’s inner life, and being rooted in the world.

DO: What are some of the books that had, for you, that kind of life-changing potential?

JC: I was very moved by The Confessions of Saint Augustine, which I was required to read. To my surprise, I identified with this great figure, as I recognized the details of his ordinary life in my own. The great self-accusation that Augustine brings to bear isn’t of a crime; it isn’t even what people often think it is, the sin of sexual license as a young man. It is the relatively mundane offense of taking an apple from somebody’s orchard. This challenge to his conscience is the beginning of a journey from that mundane experience to a very profound intuition about the place of human beings in the world.

To read Plato and Aristotle, to track the ways in which they affected the thinkers of the West-largely Christian thinkers-was a really life-changing experience for me. I was changed again by reading the Existentialists, and Albert Camus was especially important to me. The tragic quality of his life was irresistible to a young man like me, but there were patterns even in his experience that I had learned how to look for.

For example, The Confessions is structured in such a way that the climax comes when Augustine’s mother dies, and he is numb, paralyzed, frozen. He’s unable to weep for her, and he recognizes his own great flaw: his inability to accept his mother’s love. He looks back on his whole life and sees that it’s been one long flight from her. That epiphany breaks open the emotional paralysis, and he finally weeps for her. And in allowing his love for his mother to overwhelm him, and at last to feel her love, he recognizes that all along this has been God’s love. Augustine goes on to take that experience of human love and develop the first great theology of the Trinity. The gospel of John had said that God is love, but Augustine describes exactly what that could mean.

I went from The Confessions to Camus’s novel L’Etranger, where the main character is accused of murder, but what he understands to be his real crime is that his mother has just died and he was unable to weep at her funeral. Whether Camus was consciously using this image he shares with a fellow North African from 1,700 years before or not, my discovery of this common, simple intuition about the importance of love-well, for a young man who was full of feelings but not sure what to make of them, it was a liberation. To feel licensed to have these powerful feelings of openness to life, and to be told, first by Augustine, that it’s sacred, and then, by Camus, that it goes to the heart of secular human life, was a tremendous liberation-especially since I’d grown up in a Puritan culture where the basic message is that such feelings are not to be trusted.

It seems odd, but to be in a room, alone, with the door closed, reading books, encountering books, and then to understand that you can leave the room and be the person that you’ve been wanting to be all along-it was a great thing. And to go from something like that into a theological exploration of who God is-it was an unbelievably exhilarating time, and every book you read in such a context would send you into two more books.

DO: You’ve been writing novels for many years now. What inspired you at this point in your life to write a memoir?

JC: Two things: the aging and deaths of my parents, and the coming to maturity of my children. It seemed very important to me that my children should come into adulthood with a fuller sense of who their grandparents were, and in particular, of what my father’s struggle was. My children knew my father as a senile old man. That was such a source of grief to me-to see my son Patrick’s eyes cloud with fear at my father’s arrival.

I later understood that there were larger movements, as well. It’s no coincidence that while I was at work on that book, the United States of America was at the final stage of lifting the embargo on Vietnam. It took us twenty years to accomplish that, and my work was simply one person’s version of that broad, national movement. Ending the war, and my own experience of it, was also part of the motive. What I was trying to do was write this very particular story of the people of my generation, who came of age with, first, the paranoia about communism, the assumptions of the Cold War, and the dread of nuclear conflict; and then, the civil rights movement, the coming of John F. Kennedy, the coming of Martin Luther King, and the end of it all, both in the assassinations and in the war.

DO: I imagine that the act of writing An American Requiem brought you to a lot of other new insights, as well. What was your most surprising discovery?

JC: I was surprised by, and quite relieved by, the order in my life. To discover, for example, that my father’s public life begins in the act of tracking down a draft dodger who was a notorious criminal in the thirties in Chicago, and to go from that to the end of my father’s public life, when he sticks his neck out for his draft dodger son, and recognized a classic reversal in that. Such reversal is the structure of narrative. The beautiful order of it, the way it says everything, really, about the distance my father had come in this life-to discover that order was very important to me, and very moving.

And that’s just one of many, many epiphanies that I came upon in reflecting seriously on this family life story. To see the pattern-tragic, but nevertheless beautiful-that the Catholic peace movement should have played an important part in laying bare, and opposing, the crime of the Vietnam War: That was a perfect counterpoint to the way in which Cardinal Spellman and the Catholics in Saigon had laid the groundwork for the war. These patterns, by and large patterns of reversal, are built in, Aristotle says, to the human narrative impulse. To discover these patterns in my own and my family story was to draw meaning out of meaninglessness, and it was quite exhilarating.

DO: I want to ask you about a couple of passages toward the end of American Requiem. You write, “Telling our stories is what saves us. The story is enough.” And later, “The very act of storytelling, of arranging memory and invention according to the structure of narrative is, by definition, holy.” Can you talk a little bit more about your sense of storytelling as a holy act?

JC: It’s what I was saying to you before about discovering the order in what appeared to be, while going through it, a disordered and meaningless set of experiences. As a religious person, I see that order as a symbol of the order that the Creator of the Universe has planted in our lives. It’s the essence of my faith. And it’s why I’m very at home in the Biblical tradition that talks about the Word of God as the central manifestation of the way in which God is in the world. In that way the word “holy” is appropriate for me: This is what I take to be the essence of biblical faith. It’s what it means to be a part of what we call “the people of the book.”

In other words, my notion of narrative informs my faith, and my notion of faith informs my idea of what writing is for.

DO: Having said that, what do you think of Allen Tate’s observation, which you recount in your memoir, that one can have the vocation of a priest or the vocation of a writer, but not both?

JC: There are some people who’ve made a good life of the priesthood while being seriously committed writers. Daniel Berrigan is the most important example that comes to mind, and, obviously, Gerard Manley Hopkins.

But it’s no accident that Daniel Berrigan has to live in the Church as a kind of rebel. George Orwell said once, facetiously and displaying his bias, that “few Catholics have been any good as novel writers, and those that were, were bad Catholics.” It’s a bit of a joke, of course. But there’s some kind of truth to it. I left the priesthood because I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in rebellion against my boss. A writer’s final authority has, finally, to be his or her own conscience and imagination. You can’t worry about what other people are going to make of what you write. And you can’t be trying to get permission from somebody.

DO: In reading two other works that have changed your life-Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried and James Joyce’s “The Dead”-I was struck by the presence of ghosts, who play an important role in your book, as well. O’Brien’s narrator says, “We kept the dead alive with stories.” Is that, for you, another function of narrative?

JC: I’d say Tim O’Brien puts it quite beautifully. It’s not at all an accident to me that the followers of Jesus, who were in grief when He died and went away, were able to claim a new life, to feel united as a community, when they gathered to tell the story about what they had experienced of Him. It’s the story that brings Jesus back. This is a religion that is built on the impulse to tell a story.

What I love about O’Brien is the way in which he’s constantly pushing against the boundaries, in a way that I don’t, between the science of fact and the truth of the imagination. There’s an almost sinister quality to it, but nevertheless a playfulness to the author’s work in The Things They Carried, where he’s teasing the reader constantly. Is this real? No. Is this real? This is real. And at the end we say, Well, did it really happen?

And by then, of course, if O’Brien has succeeded, we’re not asking that anymore. We’re asking another question: What is the meaning of this story that we’ve just experienced? A person of faith comes to the end of a reading of the New Testament in a similar way. When you’re really ready to believe in the Good News you stop asking, Was that tomb really empty? You get beyond that question, to the question of, What is the Resurrection in my life?

Even when the story is painful, the telling of it opens us to a level of experience, a transcendent level-which is why, for me, James Joyce’s “The Dead” is so powerful. The trivial and banal socializing of the Dublin middle class is transformed into something else when Gretta tells her husband, Gabriel, the story of her first love. And even though, at one level, that’s a terrible thing for Gabriel to hear-he realizes Gretta loves the memory of this man in a way that she will never love him-that story opens Gabriel to a new realm, where he understands something about the mystery of human experience. –This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.

Buy at Amazon | Bookshop.org